Introductory Message

Dear Colleagues:

Actinic keratosis (AK) is a chronic disease resulting from deleterious effects of long-term, cumulative, epidermal exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light. UV-induced mutations in p53, ras, and p16 genes lead to the emergence of abnormal epidermal AK cells, which proliferate while avoiding apoptosis and may lead to invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

Tirbanibulin 1% ointment is approved by the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the topical field treatment of AK on the face or scalp. Potent antiproliferative and proapoptotic activities result from tirbanibulin’s unique mechanisms of action—inhibition tubulin polymerization and disruption of microtubule formation and Src kinase signaling. Tirbanibulin 1% ointment is unique in that it has the shortest effective treatment duration (5 consecutive, once-daily applications), compared to other approved field therapies of AK. This short and well-tolerated course of therapy results in very high patient adherence to the treatment regimen. Tirbanibulin is also unique among topical AK field therapies in that it carries the strongest recommendation, based on the highest level of evidence, of the American Academy of Dermatology in their guidelines of care for the treatment of AK.

In this supplement, my colleagues and I present new and emerging information on the tirbanibulin molecule and tirbanibulin 1% ointment. Ayman Grada, Daniela Berman, and I begin the supplement with an in-depth profile of the tirbanibulin molecule and tirbanibulin 1% ointment, including a description of its mechanisms of action, an overview of high-level clinical data demonstrating its efficacy and safety, and discussion on areas in which additional research would be beneficial. Following this, you’ll find three up-to-date commentaries on tirbanibulin from experts in the field. First, Todd Schlesinger discusses the impact of prior treatment on the efficacy and tolerability of tirbanibulin ointment 1% in patients with AK. Next, Neal Bhatia discusses data showing that complete clearance of AK with tirbanibulin ointment 1% is not correlated with the severity of local skin reactions. And finally, Ismail Kasujee describes results from an exploratory qualitative research initiative in the US on the impact AK has on patients’ emotional and social/functioning status.

We hope you find this supplement informative and beneficial to your clinical approach in the management of AK, and, ultimately, that this knowledge assists you in achieving optimal outcomes in your patients.

With warm regards,

Brian Berman, MD, PhD

Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida; the Center for Clinical and Cosmetic Research, Aventura, Florida

Profile of Tirbanibulin for the Treatment of Actinic Keratosis

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(10):S3–S10

by Brian Berman, MD, PhD; Ayman Grada, MD, MS; and Daniela K. Berman, AA

Dr. B. Berman is with the Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Miami, Florida, and the Center for Clinical and Cosmetic Research in Aventura, Florida. Dr. Grada is with the Department of Dermatology at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio. Ms. D. Berman is with the University of California Berkeley Plant Gene Expression Center in Berkeley, California.

Funding: Funding for this article was provided by Almirall LLC in Malvern, Pennsylvania, USA.

Financial disclosures: Dr. B. Berman is an advisory board member, investigator, consultant, and/or speaker for Biofrontera, SUN Pharmaceuticals, Inc., LEO Pharma, and Almirall LLC. Dr. Grada is a former Almirall LLC employee. Ms. D. Berman has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Actinic keratosis (AK) is a chronic disease resulting from deleterious effects of long-term, cumulative, epidermal exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light. UV-induced mutations in p53, ras, and p16 genes lead to the emergence of abnormal epidermal actinic keratosis (AKs) cells, which proliferate while avoiding apoptosis and may lead to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. There are both lesion-targeted and field-directed topical treatments. This review is of new and emerging information on tirbanibulin and tirbanibulin 1% ointment, which is approved for topical field treatment of actinic keratosis on the face and scalp. Potent antiproliferative and proapoptotic activities result from tirbanibulin’s inhibition tubulin polymerization and disruption of microtubule formation and Src kinase signaling. Tirbanibulin 1% ointment is an effective treatment of facial and scalp AK after five consecutive once-daily applications, as measured by complete and partial clearance and percent reduction in the number of lesions. Localized skin reactions are usually mild to moderate, resolving within a month. The short and well-tolerated course of therapy results in very high patient adherence to the treatment regimen

Keywords: Tirbanibulin ointment, actinic keratosis, field therapy

Actinic keratosis (AK) is a commonly occurring skin disease that results from cumulative ultraviolet (UV) irradiation.1 Estimates approximate that 60 percent of people over 40 years of age with a history of UV exposure have at least one AK lesion2 and that AK affects 58 million people in the United States, leading to treatment costs (in 2004) in excess of $1,000,000,000.3 AK is a clinical diagnosis of scaly, rough, pink-to-red papules on sun-exposed skin. Histopathologic examination is warranted when there is a concern of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).4,5

AK falls within a continuum from sun-damaged skin to AKs to in-situ SCC to invasive SCC. Intraepidermal AK cells exhibit histopathologic features detected in invasive SCC, including atypical keratinocytes, nuclear pleomorphism, and disordered keratinocyte maturation.4,6 Alterations at the molecular level in specific genes, such as p53,7-10, and changes in gene expression profiles11 confirm a similar genetic evolution of AK and SCC. Insights into the genomic landscape of actinic keratoses and their progression to cutaneous SCC (cSCC) were recently achieved with whole exome sequencing of 37 AKs. Forty-four significantly mutated AK driver genes were identified and confirmed to be similarly altered in cSCC. Integration with gene expression datasets confirmed that dysregulated of tumor growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling may represent an important event in AK to cSCC progression.7

The natural history of AK lesions encompasses regression, persistence, or progression to in-situ or invasive SCC. The overall risk of progression of an AK lesion is low; however, the disease is chronic with patients having multiple AK lesions at any point in time and developing new lesions over time, which increases a patient’s overall risk of developing invasive disease.12,13 In a study of nearly 500,000 people, half of which had AK and the other half of which were matched controls without AK, it was clearly detected that AK increased the risk of developing cSCC. The yearly risk of developing SCC was double in patients with AK (1.97% vs 0.835%) than in controls and was triple after 10 years of follow-up (17.1% vs 5.7%).14 Beyond the risk, modeled mathematically, of a patient with 7 to 8 AK lesions developing invasive SCC (6.1– 10.2% spanning 10 years),15 there are data that most SCCs arise from AK lesions, with an AK lesion being concomitant or contiguous with SCC in 65 to 97 percent of reviewed cases.13,16–18 The need to treat AK is supported by the histologic, molecular genetic, and epidemiologic relationship between AK and risk of developing SCC.5,19,20

Treatment of AK is usually classified as lesion-directed or field-directed therapy. Investigators who biopsied and examined clinically normal skin adjacent to biopsy-proven AK lesions found that in 75 percent of the “normal” skin there was histological evidence of AK. These “subclinical” lesions of AK indicate the presence of “field cancerization,” which requires field therapy, rather than solely targeted therapy, to treat not only the clinically visible but also the affected, albeit normal appearing, intervening areas between AK lesions.

Counter to the evidence that field therapy is needed to address both visible and subclinical AK lesions, targeted cryotherapy is by far the most common treatment of AK in the United States (US). Survey data representing approximately 57.9 million AK visits in the US indicated that cryotherapy was administered in 50.8 percent of AK visits and field therapies (e.g., 5-fluoruracil [5FU], imiquimod, ingenol mebutate, photodynamic therapy) in less than 3.2 percent of visits.22

For limited numbers of AK lesions, cryosurgery, most commonly utilizing liquid nitrogen as the cryogen, is effective and the most frequently used method in the US.23–25 Unfortunately, to be effective, the required duration of freezing at the extremely low temperature of liquid nitrogen is lethal to normal melanocytes in the epidermis and often results in loss of pigment in the treated areas.26 Relying on targeted treatment limited to visible lesions that avoids perilesional subclincal lesions results in significant recurrences, which may be due, in part, to subclinical AK lesions becoming visible AKs over time.27–29

United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved field therapies, which include 5FU, imiquimod, diclofenac, and tirbanibulin, address field cancerization in AK by eliminating transformed cells in the treated field. It is not surprising that during such field treatments new visible lesions that were not present at baseline arise and resolve, suggesting effectiveness for subclinical lesions.28,30,31 Patient adherence is challenging due to required large number of applications (as many as 180) and prolonged (up to 4 months) treatment and to the resulting localized erythema, scaling, edema, erosions, and discomfort (e.g., burning, itching). To achieve greater patient adherence and persistence, greater regimen simplicity and greater tolerability has been the goal of using modified dosing schedules, lower drug concentrations, and novel formulations,31–33 as well as sequential treatment employing both lesion- and field-directed methods, to achieve greater effectiveness.34–40

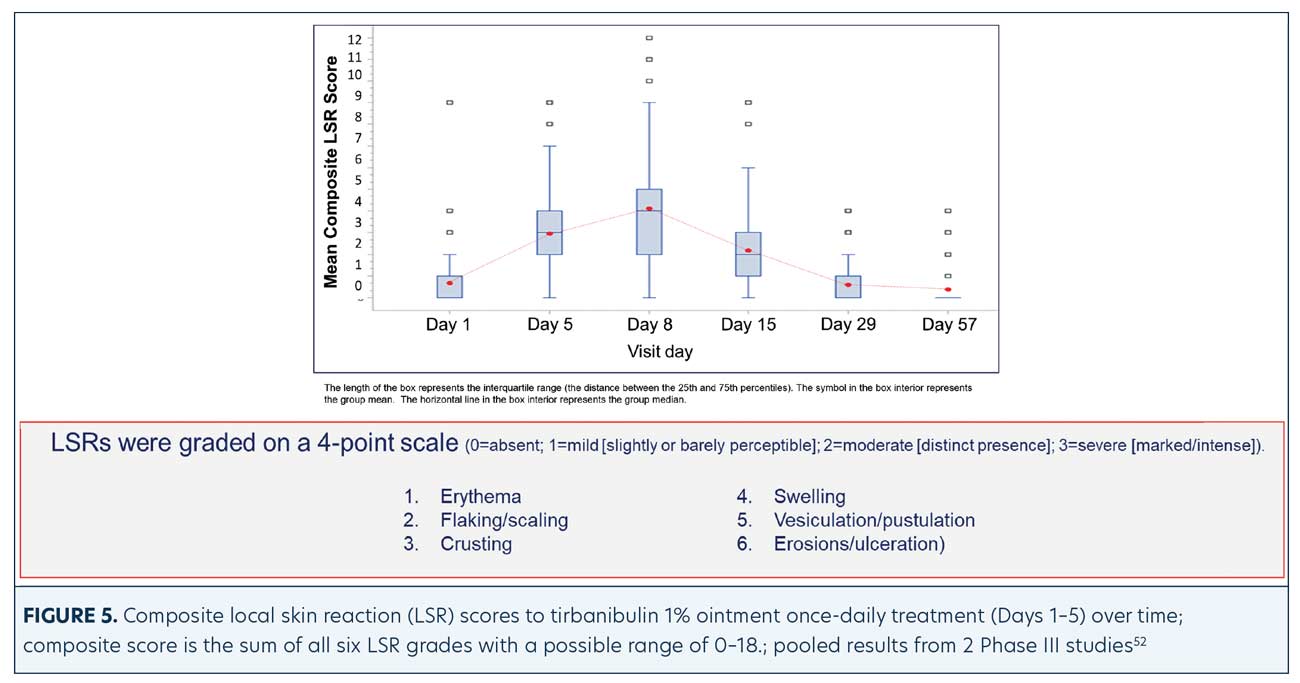

Shergil et al41 reported that the majority (63%) of patients being treated topically for AKs did not adhere to their treatment regimen, primarily due to local skin reactions and treatment being excessive and not simple. Experts have suggested that keeping AK field treatment short and simple could improve patient adherence.41,42 Of the available US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved, topically applied AK field therapies and dosing regimens, the number of applications range from as few as two to as many as 180 and require up to four months duration of therapy. Following ingenol mebulate, with its once-daily application for 2 to 3 days, being removed from the market, tirbanibulin 1% ointment, approved for once-daily application for five consecutive days, is the shortest topical AK therapy available. Ninety-nine–percent patient adherence rates have been reported in large Phase III studies using this short, simple regimen of tirbanibulin 1% ointment. The mostly mild-to-moderate severity local skin reactions (LSRs) reported in these studies peak at three days following completion of all applications and quickly resolve.

This article reviews the mechanisms of action of tirbanibulin and highlights clinical studies and data supporting the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and patient acceptance of tirbanibulin 1% ointment for the treatment of AK.

Mechanisms of Action

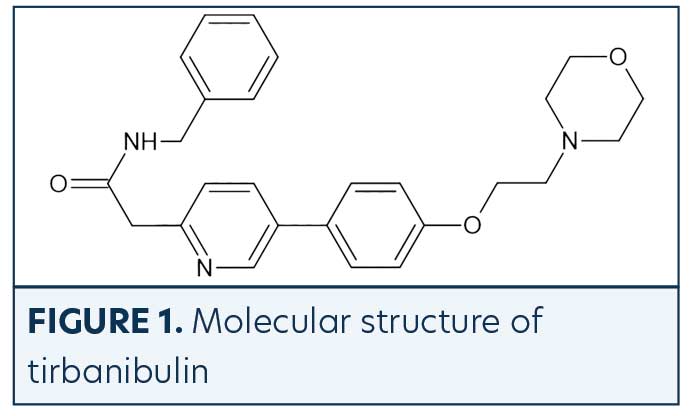

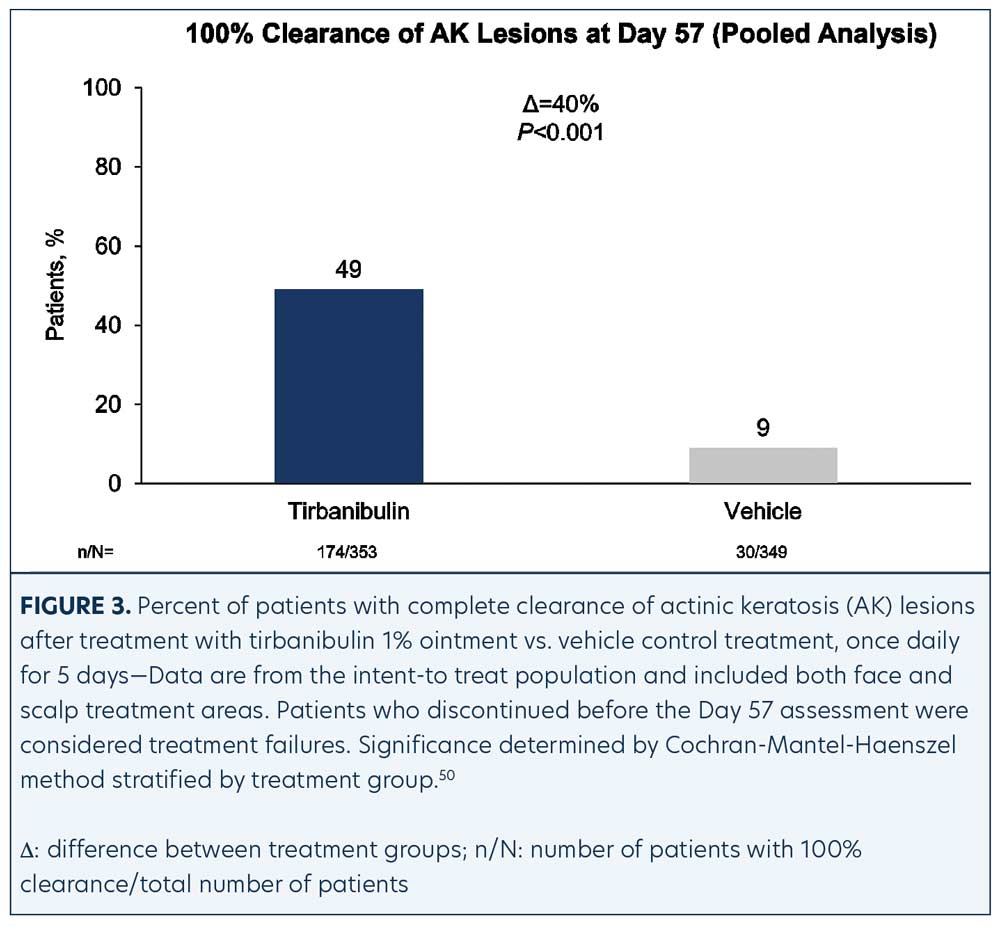

Tirbanibulin is a novel synthetic chemical entity (Figure 1) that has shown potent antiproliferative and antitumoral effects in vitro and in vivo by inducing cell cycle arrest and ultimately apoptotic cell death. These effects have been attributed to the ability of tirbanibulin to reversibly bind to the colchicine-binding site on β-tubulin43 and inhibit tubulin microfilament polymerization (Figure 2).44 Additional studies are needed to confirm whether tirbanibulin also binds to β-tubulin and/or a novel site on the α−β-tubulin heterodimer.44 Immunofluorescence staining has shown that tirbanibulin effectively disrupts the cellular MTs network immortalized keratinocyte CCD 1106 KERTr cells and HeLa cells. Tirbanibulin appears to induce complete cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase43 and trigger signals of programmed cell death by activating both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways via Bcl-2, cleavage of caspase 8 and 9, and activation of caspase 3, in colon cancer HT-29 cells.

Src family kinases (SFKs) are a family of nine nonreceptor tyrosine kinases45 involved in vascular epithelial growth factor and angiogenesis.46,47 Elevated Src expression has been observed in AK and SCC, suggesting that increased signaling is necessary for keratinocyte migration and squamous carcinoma invasion.48 Tirbanibulin was shown to significantly down-regulate phospho-Src (p-Src) and Src signaling molecules and disrupt SFKs signaling in various cancer cell lines and tumor xenografts in mice.49 Whether the effects of tirbanibulin on Src signaling result from its direct binding to Src or secondary to its disruption of cellular microtubule networks is unclear.

Clinical Data

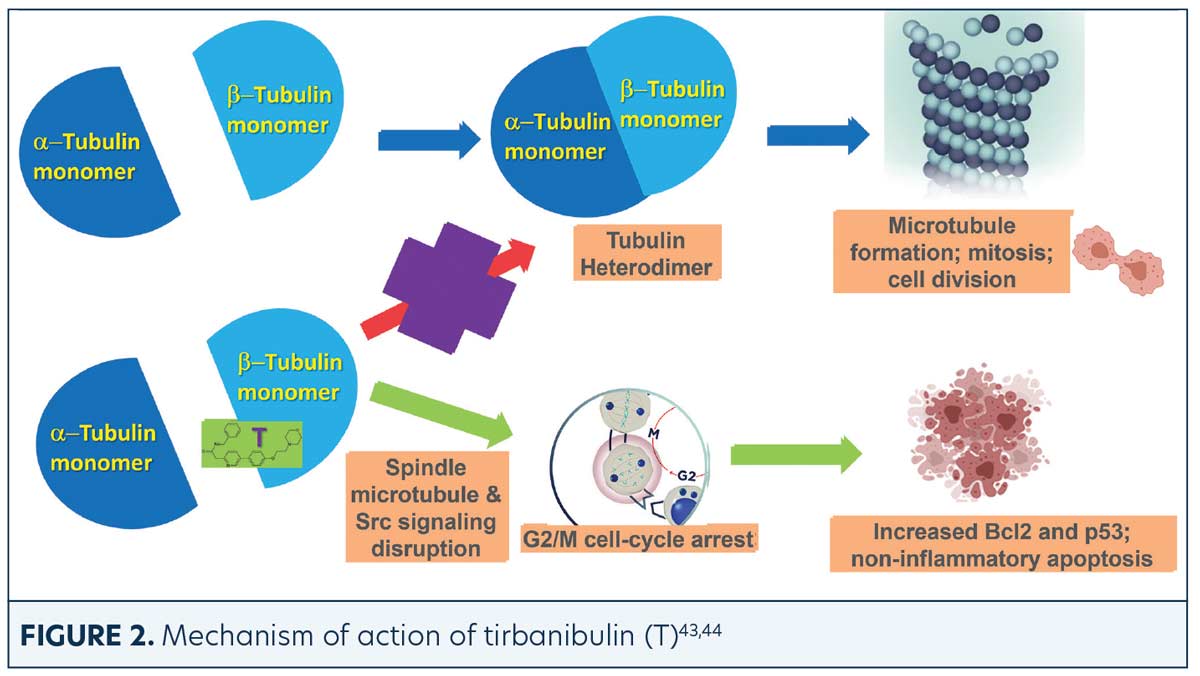

Over 700 adult patients with 4 to 8 nonhypertrophic AKs in a contiguous area of 25cm2 on the face (68%) or scalp (32%) were randomized (1:1) in two identical Phase III trials to determine the tolerability and efficacy of tirbanibulin 1% ointment for AK compared to the ointment vehicle.50 The trials were carried out with the subjects and investigators/evaluators blinded to the randomized treatment. The average composite subject was a 70-year-old man with Fitzpatrick Skin Type I or II with facial AKs. Subjects received five consecutive days of once-daily treatment to the targeted 25cm2 field with either tirbanibulin (n=353) or vehicle control (n=349). Subjects with complete (100%) clearance of AK lesions in the treatment area at Day 57 were assessed for AK lesion recurrence every three months for a total of 12 months post-Day 57.

The primary efficacy endpoint was complete (100%) clearance of AK lesions in the treatment area, defined as the proportion of subjects at Day 57 with no clinically visible AK lesions in the treatment area, and the secondary endpoint was partial (≥75%) clearance of AK lesions in the treatment area.

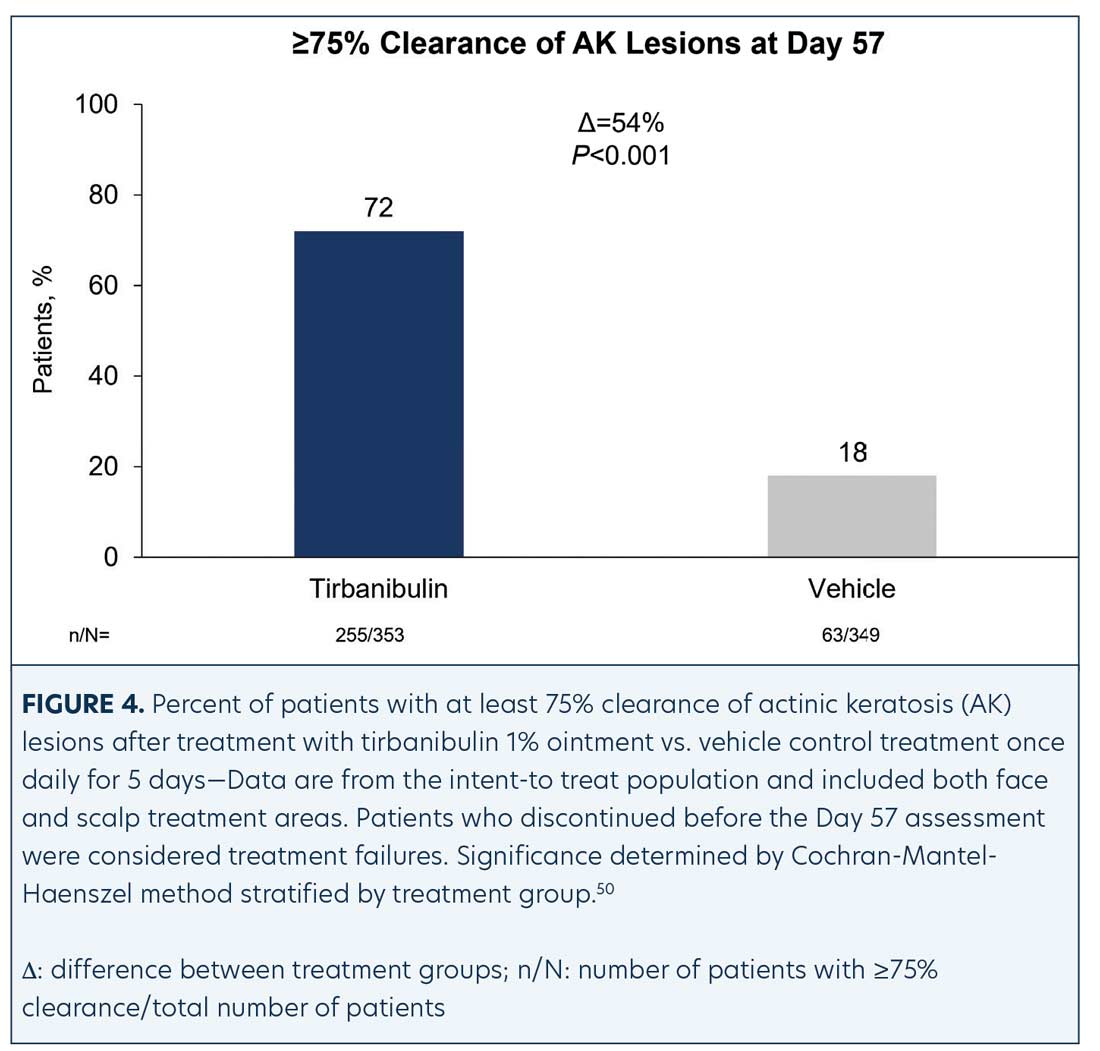

Efficacy (pooled). Statistically significant higher Day 57 clinical endpoint complete and partial responses (Figures 3 and 4) were achieved in those receiving tirbanibulin treatment compared to those receiving vehicle. Median percent reduction from baseline, an important, unique endpoint being independent of the starting number of AK lesions, was higher (83%) in the active treatment arm compared with vehicle (20%).50

Consistent with the knowledge that AK lesions on the face have been found to be more responsive to all approved field therapies than AK lesions on the scalp, tirbanibulin treatment also exhibited significantly enhanced effectiveness rates on facial AK lesions than on scalp AK lesions, compared to vehicle (Table 1). Subgroup analyses revealed the efficacy of tirbanibulin to be consistent across sex and in those above or below 65 years of age.50

Phototoxicity and contact sensitization. Clinical studies in healthy subjects have reported that tirbanibulin ointment did not cause contact sensitization (n=261), phototoxic skin reactions (n=31), or photoallergic skin reactions (n=64).51

Safety (pooled). Treatment-related adverse events (AEs). AEs were few and mostly mild transient application-site pruritus (tirbanibulin vs. vehicle: 9% vs. 6%) and pain (tirbanibulin vs. vehicle: 10% vs. 3%) (Table 2). No deaths, discontinuations, or serious AEs related to tirbanibulin occurred.50,51

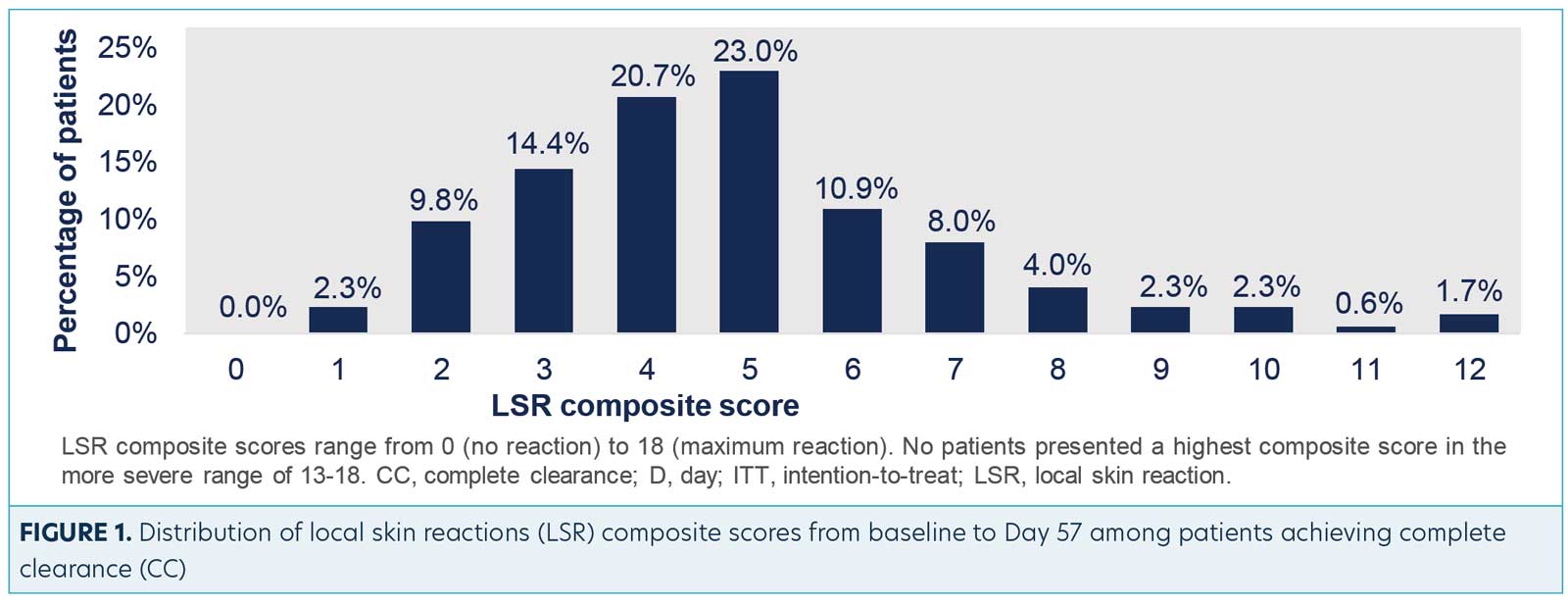

LSRs. LSRs were collected independent of AEs and included erythema, flaking/scaling, crusting, swelling, vesiculation/pustulation, and erosions/ulcerations. LSRs were assessed by the investigators using a four-point grading scale of 0=absent, 1=mild (slightly, barely perceptible), 2=moderate (distinct presence), and 3=severe (marked, intense). Composite score was the sum of all six LSR grades with a possible range of 0 to 18.50 Incidence and severity of LSRs greater than baseline was higher with tirbanibulin versus vehicle. LSRs were mostly mild to moderate, with severe reactions observed in less than 10 percent of subjects receiving tirbanibulin.51 LSRs peaked on Day 8 with tirbanibulin, decreased significantly by Day 15, and completely resolved by Days 29 to 57 (Figure 5). No significant difference was observed in LSR severity in patients younger or older than 65 years of age. No patients discontinued the study due to LSRs.50,52 Complete clearance of AKs using tirbanibulin 1% ointment was associated with mild-to-moderate LSRs, with 70.2 percent of patients showing a composite LSR score of 5 or less, highlighting that complete clearance was not correlated with the severity of LSRs.53

A post-hoc analysis of the two Phase III clinical trials, in which 353 participants having 4 to 8 clinically visible AK lesions (25cm2 area) were randomized to receive tirbanibulin (self-applied once daily, 5 consecutive days) was performed to assess the clearance rates of facial and scalp AK following treatment with tirbanibulin ointment 1% in different patient subgroups by body mass index (BMI), Fitzpatrick skin type, and previous AK treatment. There was no statistically significant relationship between the baseline variables of previous AK treatment (Table 3), Fitzpatrick skin type (Table 4), or BMI (29kg/m2) (Table 5) and complete (100%) and partial (>75%) clearance (CC, PC) at Day 57. In contrast, although found to be effective for both facial and scalp AK lesions, their location on the face did predict greater CC and PC success rates after two months.54

Additional post-hoc analyses of the two Phase III clinical trials evaluated CC and PC rates of AKs and severity of LSRs at time points (Day 8 earlier than end of study Day 57). At study visits (Days 8–15 to Days 29–57) CC, PC, and LSRs, including erythema, flaking/scaling, crusting, swelling, vesiculation/pustulation, and erosion/ulceration, were assessed. Each LSR was scored between 0 and 3 (0=absent, 3=severe). Individual scores were added together, resulting in a LSR composite score between 0 and 18. The maximum LSR composite scores reached up to Day 57 were averaged for participants achieving CC at each visit.

A CC rate of 13.4 percent was achieved at Day 8, increasing during treatment to 24.7 percent (Day 15), 36.4 percent (Day 29), and 49.3 percent (Day 57). PC rate was 20.2 percent at Day 8 and gradually rose to 41.2 percent (Day 15), 62.8 percent (Day 29), and 72.2 percent (Day 57). Among patients reaching CC at each visit, baseline characteristics were similar except for a trend to higher percentage of face treatments in those achieving CC at Days 8 to 15 versus Days 29 to 57. The mean (±standard deviation) maximum LSR composite score reached during the follow-up was similarly low regardless of whether CC was obtained at Day 8 (4.7±1.8), Day 15 (4.8±2.2), Day 29 (4.9±2.1), or Day 57 (4.9±2.1). Although the highest CC rate with tirbanibulin was observed at Day 57, this analysis confirms that patients with AK can show much earlier responses (from Day 8). These were not accompanied by an increase in the severity of LSRs.55

Recurrence. For the one-year follow-up study, 174 subjects treated with tirbanibulin 1% ointment for once daily for five days who achieved CC at Day 57 were included. Post-hoc analysis of Kaplan-Meier estimates showed that at one year, 53 percent of patients maintained CC from recurrent lesions. The Kaplan-Meier estimate indicated that 27 percent remained free of any new or recurrent AK lesions in the 25cm2 treated area up to one year. Patients who had more than five baseline AK lesions [OR 2.1] or had prior AK treatments to the study treatment area [OR 3.0] correlated with recurrence of any AKs. Importantly, no skin cancers were detected in the treatment area throughout the one-year follow-up period.50

Based upon these studies, tirbanibulin was approved by the FDA as a field therapy for AK with the application of 2.5mg tirbanibulin in 250mg ointment to a 25cm2 contiguous area of skin on the face or scalp once daily for five consecutive days.51 The FDA accepts the defined 25cm2 area as a “field” of AK lesions, but in clinical practice, treatment requires a greater area. In a recent report, a single packet of 2.5mg tirbanibulin dissolved in 250mg ointment was sufficient to be evenly applied to a patient’s balding scalp, forehead, and two facial target AK lesions, for a total area of 317.82cm2 (digitally measured).56 As expected, LSRs peaked at Day 8 in the treatment areas and resolved by Day 39, similar to the findings in the Phase III trials. Presence of LSRs which peaked at Day 8 and resolved by Day 39 and clearance of the two target AK lesions (last to be treated at each of the 5 consecutive once-daily applications) suggest that the thin layer of ointment applied to this large area was sufficient to penetrate and be effective.56

Additional Considerations

Recently, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) released a focused update of its guidelines of care for the management of AK.57 In this update, tirbanibulin is unique among all other listed topical treatments of AKs, in that it received the AAD AK guidelines committee’s strongest recommendation based on the highest certainty of evidence. The use of other field therapies, including imiquimod and ingenol mebutate, following cryotherapy of AK with liquid nitrogen, have resulted in additional benefits. We look forward to future studies to determine the effectiveness and safety of sequential treatment of AK with targeted cryotherapy followed by tirbanibulin 1% ointment.

An active comparator study of the efficacies and tolerabilities of tirbanibulin 1% ointment versus 5FU preparations would help direct the clinical choice of AK treatment. If such studies are undertaken, the following caveat regarding extemperaneous 5FU preparations should be noted. Investigators compared the efficacy and tolerability of 5% 5 fluorouracil cream + 0.005% calcipotriol ointment combination (FU+C) with 5% 5FU + petroleum jelly (Vaseline®, Unilever plc., London, England, United Kingdom) combination (FU+V) in the treatment of actinic keratoses.58 The FU+V control resulted in zero percent of participants having CC of facial AKs and an unexpectedly low four percent developing severe erythema, possibly due to the added petroleum jelly interfering with FU absorption. A recent study comparing the skin absorption and penetration of four different 5% 5FU formulations, including FU+V, found that combining 5FU cream with petroleum jelly interfered with the 5FU penetration through skin, resulting in a 20-fold reduced eight-hour penetration of 5FU when in the presence of petroleum jelly compared to 5% 5FU cream, and a 73-percent reduction in 5FU penetration compared to the 5-FU + calcipotriol ointment combination.59 These findings point to the inappropriateness of using 5FU in petroleum jelly as a control for clinical studies, which could lead to erroneous superiority claims.

Human papillomavirus 16 (HPV 16) has been detected in periungual SCCs and the HPV 16 E7 oncoprotein up-regulates Src family kinases, which tirbanibulin has been found to inhibit. Therefore, it is intriguing, albeit not surprising, that tirbanibulin 1% ointment has been reported to be effective in the treatment of in-situ cSCC.60 As previously discussed, SCC falls in the AK-to-SCC continuum, and therefore this possible indication for its treatment with tirbanibulin should be pursued further.

In Summary

Tirbanibulin 1% ointment is novel as a topical field therapy for AK, both in its mechanisms of action and short treatment duration. Its antiproliferative and proapoptotic activities result in an 83-percent median reduction in the number of AK lesions from baseline. It does so in a relatively noninflammatory fashion, with LSRs being rated as mostly mild to moderate. Importantly, the contents of a single packet of tirbanibulin 1% ointment were measured to cover more than the FDA-approved area of 25cm2, while maintaining effectiveness. At one year following once daily treatment for five days, 53 percent of the patients maintained 100-percent clearance, without recurrence of any of treated AK lesions. The findings outlined in this review suggest that tirbanibulin 1% ointment is a valuable, effective, and safe addition to our treatment armamentarium for AK.

References

- Uhlenhake EE. Optimal treatment of actinic keratoses. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:29.

- Drake LA, Ceilley RI, Cornelison RL, et al. Guidelines of care for actinic keratoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(1):95–98.

- Society for Investigative Dermatology, American Academy of Dermatology Association. The burden of skin diseases, 2005. https://www.lewin.com/content/dam/Lewin/Resources/Site_Sections/Publications/april2005skindisease.pdf. Accessed 2 Feb 2022.

- Cockerell CJ, Wharton JR. New histopathological classification of actinic keratosis (incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma). J Drug Dermatol. 2005;4(4):462–467.

- Berman B, Bienstock L, Kuritzky L, et al. Actinic keratosis: sequelae and treatments: recommendations from a consensus panel. J Fam Pract. 2006;55(5):S1–S1.

- Schwartz RA. The actinic keratosis: a perspective and update. Dermatolog Surg. 1997;23(11):1009–1019.

- Thomson J, Bewicke-Copley F, Anene CA, et al. The genomic landscape of actinic keratosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141(7):1664–1674.e7.

- Toll A, Salgado R, Yebenes M, et al. MYC gene numerical aberrations in actinic keratosis and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(5):1112–1118.

- Toll A, Salgado R, Yébenes M, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene numerical aberrations are frequent events in actinic keratoses and invasive cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. Exp dermatol. 2010;19(2)

151–153. - Kanellou P, Zaravinos A, Zioga M, et al. Genomic instability, mutations and expression analysis of the tumour suppressor genes p14ARF, p15INK4b, p16INK4a and p53 in actinic keratosis. Cancer Lett. 2008;264(1):145–161.

- Padilla RS, Sebastian S, Jiang Z, et al. Gene expression patterns of normal human skin, actinic keratosis, and squamous cell carcinoma: a spectrum of disease progression. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(3):

288–293. - Marks R, Foley P, Goodman G, et al. Spontaneous remission of solar keratoses: the case for conservative management. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115(6):649–655.

- Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention trial. Cancer. 2009;115(11):2523–2530.

- Madani S, Marwaha S, Dusendang JR, et al. Ten-year follow-up of persons with sun-damaged skin associated with subsequent development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(5):

559–565. - Dodson JM, DeSpain J, Hewett JE, Clark DP. Malignant potential of actinic keratoses and the controversy over treatment: a patient-oriented perspective. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127(7):1029–1031.

- Czarnecki D, Meehan C, Bruce F, Culjak G. The majority of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas arise in actinic keratoses. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6(3):207–209.

- Mittelbronn MA, Mullins DL, Ramos-Caro FA, Flowers FP. Frequency of pre-existing actinic keratosis in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(9):677–681.

- Hurwitz RM, Monger LE. Solar keratosis: an evolving squamous cell carcinoma. benign or malignant? Dermatolog Surg. 1995;21(2):184.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer Jr AB. Progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma revisited: clinical and treatment implications. Cutis. 2011;87(4):201–207.

- Stockfleth E, Ferrandiz C, Grob JJ, et al. Development of a treatment algorithm for actinic keratoses: a European consensus. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18(6):651–659.

- Markowitz O, Wang K, Levine A, et al. Noninvasive long-term monitoring of actinic keratosis and field cancerization following treatment with ingenol mebutate gel 0.015%. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10(10):28.

- Ranpariya VK, Muddasani S, Mahon AB, Feldman SR. Frequency of procedural and medical treatments of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(4):916–918.

- Dinehart SM. The treatment of actinic keratoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1):S25–S28.

- Halpern AC, Hanson LJ. Awareness of, knowledge of and attitudes to nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and actinic keratosis (AK) among physicians. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(9):638–642.

- Balkrishnan R, Cayce KA, Kulkarni AS, et al. Predictors of treatment choices and associated outcomes in actinic keratoses: results from a national physician survey study. J Dermatologic Treat. 2006;17(3):162–166.

- Thai KE, Fergin P, Freeman M, et al. A prospective study of the use of cryosurgery for the treatment of actinic keratoses. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(9):687–692.

- Krawtchenko N, Roewert-Huber J, Ulrich M, et al. A randomised study of topical 5% imiquimod vs. topical 5-fluorouracil vs. cryosurgery in immunocompetent patients with actinic keratoses: a comparison of clinical and histological outcomes including 1-year follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:

34–40. - Tanghetti E, Werschler P. Comparison of 5% 5-fluorouracil cream and 5% imiquimod cream in the management of actinic keratoses on the face and scalp. J Drugs in Dermatol. 2007;6(2):144–147.

- Ulrich M, Krueger-Corcoran D, Roewert-Huber J, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy for noninvasive monitoring of therapy and detection of subclinical actinic keratoses. Dermatology. 2010;220(1):15–24.

- Rivers J, Arlette J, Shear N, et al. Topical treatment of actinic keratoses with 3· 0% diclofenac in 2· 5% hyaluronan gel. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(1):94–100.

- Swanson N, Abramovits W, Berman B, et al. Imiquimod 2.5% and 3.75% for the treatment of actinic keratoses: results of two placebo-controlled studies of daily application to the face and balding scalp for two 2-week cycles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(4):582–590.

- Loven K, Stein L, Furst K, Levy S. Evaluation of the efficacy and tolerability of 0.5% fluorouracil cream and 5% fluorouracil cream applied to each side of the face in patients with actinic keratosis. Clinic Therapeut. 2002;24(6):990–1000.

- Werschler WP. Considerations for use of fluorouracil cream 0.5% for the treatment of actinic keratosis in elderly patients. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2008;1(2):22.

- Lee AD, Jorizzo JL. Optimizing management of actinic keratosis and photodamaged skin: utilizing a stepwise approach. Cutis. 2009;84(3):169–175.

- Eisen DB, Asgari MM, Bennett DD, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(4):e209–e233.

- Serra-Guillén C, Nagore E, Hueso L, et al. A randomized pilot comparative study of topical methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy versus imiquimod 5% versus sequential application of both therapies in immunocompetent patients with actinic keratosis: clinical and histologic outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(4):e131–e137.

- Berlin JM, Rigel DS. Diclofenac sodium 3% gel in the treatment of actinic keratoses postcryosurgery. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(7):669–673.

- Tan JK, Thomas DR, Poulin Y, et al. Efficacy of imiquimod as an adjunct to cryotherapy for actinic keratoses. J Cutan Med Surg. 2007;11(6):195–201.

- Jorizzo JL, Markowitz O, Lebwohl MG, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicenter, efficacy and safety study of 3.75% imiquimod cream following cryosurgery for the treatment of actinic keratoses. J Drug Dermatol. 2010;9(9):

1101–1108. - Jorizzo J, Weiss J, Vamvakias G. One-week treatment with 0.5% fluorouracil cream prior to cryosurgery in patients with actinic keratoses: a double-blind, vehicle-controlled, long-term study. J Drug Dermatol. 2006;5(2):133–139.

- Shergill B, Zokaie S, Carr AJ. Non-adherence to topical treatments for actinic keratosis. Patient Preference Adherence. 2014;8:35.

- Grada A, Feldman SR, Bragazzi NL, Damiani G. Patient-reported outcomes of topical therapies in actinic keratosis: a systematic review. Dermatolog Ther. 2021;34(2):e14833.

- Niu L, Yang J, Yan W, et al. Reversible binding of the anticancer drug KXO1 (tirbanibulin) to the colchicine-binding site of β-tubulin explains KXO1’s low clinical toxicity. J Biologic Chem. 2019;294(48):18099–18108.

- Smolinski MP, Bu Y, Clements J, et al. Discovery of novel dual mechanism of action Src signaling and tubulin polymerization inhibitors (KX2-391 and KX2-361. J Med Chem. 2018;61:4707–4719.

- Frame MC. Src in cancer: deregulation and consequences for cell behaviour. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) Review Cancer. 2002;1602(2):114–130.

- Irby RB, Yeatman TJ. Role of Src expression and activation in human cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19(49):5636–5642.

- Munshi N, Groopman JE, Gill PS, Ganju RK. c-Src mediates mitogenic signals and associates with cytoskeletal proteins upon vascular endothelial growth factor stimulation in Kaposi’s sarcoma cells. J Immunol. 2000;164(3):1169–1174.

- Ainger SA, Sturm RA. Src and SCC: getting to the FAK s. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24(7):487–488.

- Kim S, Min A, Lee K-H, et al. Antitumor effect of KX-01 through inhibiting Src family kinases and mitosis. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49(3):643.

- Blauvelt A, Kempers S, Lain E, et al. Phase 3 trials of tirbanibulin ointment for actinic keratosis. N Eng J Med. 2021;384(6):512–520.

- Klisyri ointment. Package insert. Almirall, LLC. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/213189s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 2 Feb 2022.

- Schlesinger T, Bhatia N, Berman B, et al. Favorable safety profile of tirbanibulin ointment 1% for actinic keratosis: pooled results from two Phase III studies. SKIN J Cutan Med. 2020;4(6):s120–s120.

- Berman B, Schlesinger T, Bhatia N, et al. Complete clearance of actinic keratosis with tirbanibulin ointment 1% is not correlated with the severity of local skin reactions. Poster presentation. Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference 2021; Las Vegas, NV, USA.

- Berman B, Gual A, Grada A, et al. Efficacy of tirbanibulin ointment 1% across different patient populations: pooled results from two Phase 3 studies. Poster presentation. Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference. 3–5 Jun 2022. Scottsdale, AZ, USA

- Berman B, Gupta G, Laura Padullés L, et al. Complete clearance of actinic keratosis observed from Day 8 of tirbanibulin treatment, along with good tolerability: post-hoc analysis of two Phase 3 studies. Poster Presentation. Society for Investigative Dermatology Annual Meeting; 18–21 May 2022. Portland, OR, USA.

- Dunn A, Han H, Gade A, Berman B. Determination of the area of skin capable of being covered by the application of 250mg of tirbanibulin ointment, 1%. SKIN J Cutan Med. 2021;5(6):s82–s82.

- Eisen DB, Dellavalle RP, Frazer-Green L, et al. Focused update: guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(2):373–374.

- Cunningham TR, Tabacchi M, Eliane J-P, et al. Randomized trial of calcipotriol combined with 5-fluorouracil for skin cancer precursor immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:

106–116. - Berman B, Tomondy P. Skin absorption and penetration study of four different topical formulations of 5-fluorouracil. SKIN J Cutan Med. 2022;in press.

- Moore A, Moore S. Topical tirbanibulin eradication of periungual squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol Case Rep. 2021;101–103.

Commentary: Impact of Prior Treatment in the Efficacy and Tolerability of Tirbanibulin Ointment 1% for Actinic Keratosis: Pooled Results from Two Phase III Studies

J Clin Aestet Dermatol. 2022;15(10):S11–S12

by Todd Schlesinger, MD, FAAD

Dr. Schlesinger Affiliate Assistant Professor, Medical University of South Carolina College of Medicine Affiliate Assistant Professor, Medical University of South Carolina College of Health Professions; and Clinical Instructor, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Funding: Funding for this article was provided by Almirall LLC in Malvern, Pennsylvania, USA.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Schlesinger is a consultant/speaker for Sun Pharmaceuticals and an advisor, consultant, and investigator for Almirall, Biofrontera, Galderma and Abbvie.

In 2021, two Phase III, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies were completed evaluating tirbanibulin ointment 1% as a field treatment for actinic keratosis (AK).1 A post-hoc analysis of pooled results from the two Phase III trials was conducted to determine if there would be differences in efficacy and tolerability among groups stratified by prior AK treatment.2

The Phase III trials accounted for patients showing 4 to 8 clinically visible AK lesions within a 25cm2 area. The patients were randomized with a 1:1 ratio into two groups. Both groups consisted of a double-blind treatment labeled either tirbanibulin ointment 1% or vehicle.1 For the post-hoc analysis, the complete (100%) clearance (CC) rate, defined as the proportion of patients with no clinically visible lesions, and the partial (≥ 75%) clearance (PC) rate, defined as the proportion of patients with at least a 75-percent reduction in lesions, were used when quantifying the pooled data. The post-hoc analysis showed CC and PC rates of 49 percent and 72 percent, respectively, for tirbanibulin-treated participants versus nine percent and 18 percent, respectively, for vehicle-treated participants. Both treatments were self-applied by the participants once daily for five consecutive days. Alongside the self-applied treatment, the clinically visible lesions were counted at different time points on all patients throughout the study. A distinction was made for patients previously treated for AK either through cryosurgery or topicals—these patients were defined as “pretreated.” The patients’ conditions within the areas of interest were rated on a severity scale ranging from 0 to 3 (0=absent, 3=severe) for observation of local skin responses (LSR) displaying erythema, flaking/scaling, crusting, swelling, vesiculation/pustulation, or erosions/ulceration. A sum of these scores was calculated for each patient (scores ranged from 0–18) with an averaged maximum composite score for each study period.2

Results of the post-hoc study indicated that the proportion of pretreated patients in the tirbanibulin and vehicle groups were 37 percent and 40 percent, respectively. Of those pretreated patients, 70 percent received cryosurgery and 35 percent received topicals in the treatment area. Tirbanibulin treatment resulted in CC of 45.1 percent for patients pretreated with cryosurgery and 33.3 percent for patients pretreated with topicals. Moreover, tirbanibulin treatment achieved PC in 71.4 percent of patients pretreated with cryosurgery and 60.0 percent of patients pretreated with topicals. The LSR composite scores showed similarities between test groups and pretreatment groups. The LSR scores of overall pretreated, cryosurgery, topical, and non-pretreated groups from the tirbanibulin and vehicle populations were compared to one another. The conclusion reached is that there was no significant difference between mean LSR composite scores between the two populations.2

Similar studies have been conducted to test tirbanibulin as a treatment for AK. A pharmacokinetic (PK) and safety study was conducted in which tirbanibulin ointment was administered to a 25cm2 area for five consecutive days.3 Eighteen participants with at least 4 to 8 clinically visible AK lesions were divided into two nonrandom, uncontrolled treatment groups. Most subjects (15 out of 18) had previous AK treatment histories, which included liquid nitrogen, 5-fluorouracil/Efudex, cryosurgery, investigational products, and local excision/curettage. Results of this study indicate that tirbanibulin ointment 1%, administered once daily for five days, for treatment of AK lesions on the face or scalp was well tolerated.3

Comparatively, treatments including 5% fluorouracil cream, 5% imiquimod cream, methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy (MAL-PDT), and 0.015% ingenol mebutate gel have been implemented into studies evaluating treatments for AK.4 A specific study testing each treatment and comparing the results included 624 patients who were divided into four treatment groups in a 1:1:1:1 ratio. The study was a single-blind, multicentered design in which observations of AK lesions over a 12-month period were noted. Results indicated that 5% fluorouracil cream was the superior treatment, with a 75.3-percent success rate (≥75% clearance) in patients in that treatment group. The other treatments of imiquimod, PDT, and ingenol mebutate resulted in success rates of 52.6 percent, 38.7 percent, and 30.2 percent, respectively.4

Fluorouracil cream 5% was also compared to 0.5% fluorouracil cream to determine which formula was more effective as a treatment for AK lesions.5 Complete clearance rates of 0.5% 5-fluorouracil cream ranged from 14.9 percent (1 week treatment) to 57.8 percent (4 weeks treatment). Complete clearance rates of the 5% formulation ranged from 43 percent (4 weeks treatment) to 100 percent (2 weeks treatment). While results suggest that 5% fluorouracil is superior to the 0.5% formulation, further investigation is required.5

This post-hoc analysis2 of two Phase III trials concluded that while the safety and efficacy of tirbanibulin ointment 1% allow it to be considered as a first-line treatment for AK, further research and clinical trials are needed to determine the most suitable treatment for AK. The comparison of LSR composite scores of two populations—tirbanibulin-treated patients and vehicle-treated patients—showed no significant difference in the tolerability of the treatments. The tirbanibulin treatment group also displayed higher levels of CC and PC in pretreated patients, compared to the vehicle-treated group. The difference in CC and PC rates support the conclusion that tirbanibulin ointment 1% is superior to vehicle at the time point of data collection (57 days).2

References

- Blauvelt A, Kempers S, Lain E, et al. Phase 3 trials of tirbanibulin ointment for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:512–520

- Schlesinger T, Bhatia, N, Berman B, et al. Impact of prior treatment in the efficacy and tolerability of tirbanibulin ointment 1% for actinic keratosis: pooled results from two phase 3 studies. Poster presentation. Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference for PAs & NPs. Orlando, FL: 12–14 Nov 2021.

- Yavel R, Overcash JS, Cutler D et al. Phase 1 maximal use pharmacokinetic study of tirbanibulin ointment 1% in subjects with actinic keratosis. Clin Pharmacol Drug Develop. 2022;11:

397–405. - Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(10):935-946.

- Kaur RR, Alikhan A, Maibach HI. Comparison of topical 5-fluorouracil formulations in actinic keratosis treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21(5):267–272.

Commentary: Complete Clearance of Actinic Keratosis with Tirbanibulin Ointment 1% is not Correlated with the Severity of Local Skin Reactions

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2022;15(10):S13–S14

by Neal Bhatia, MD

Dr. Bhatia is Director of Clinical Dermatology, Therapeutics Clinical Research, in San Diego, California.

Funding: Funding for this article was provided by Almirall LLC in Malvern, Pennsylvania, USA.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Bhatia is an advisor, consultant, and investigator for Almirall LLC.

Historically, treatment of actinic keratosis (AK) has been summarized by the old adage, “No pain, no gain.” The current treatment paradigm for AKs has been limited by aggressive and often intolerable local skin reactions (LSRs) associated with the topical therapies, instead of improvement outcomes. This has left many dermatologists relying solely on procedures for AK destruction, which are often incomplete in treating the process that leads to development of more AKs.1 Sadly this movement has been promoted by patient preferences, limited access to therapies, and incomplete counseling measures by dermatologists in regard to mitigating associated LSRs and improving tolerability of the topical AK treatments.2

On the other hand, while patients are not often willing to take the risk of appearing red or peeling for even a short treatment course of topical therapy, other modes of AK treatment may still cause them frustration. For example, cryotherapy is painful and can result in dyschromia;2 and despite its efficacy in treating existing AKs and reducing recurrence potential, photodynamic therapy can be just as uncomfortable to patients and is not available in many dermatology practices. Nevertheless, AK remains a very common dermatological problem. In 2015, more than 35.6 million actinic keratosis lesions were treated, increasing from 29.7 million in 2007. According to the United States Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), treated AKs per 1,000 beneficiaries increased from 917 in 2007 to 1,051 in 2015, while mean inflation-adjusted payments per 1,000 patients decreased from $11,749 to $10,942 owing to reimbursement cuts.3 The take-home message here is that treating AK to clearance is not happening in the real world.

The most recent American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines for the treatment of AKs4 suggests that previous topical agents, used alone or in combination with destructive procedures, are endorsed with mixed strength. Tirbanibulin 1% ointment was unique among all topical AK treatments in that it received the AAD’s highest recommendation based on the highest level of evidence, its shorter treatment cycle, and its more tolerable LSRs. As an aside, it was not possible to endorse tirbanibulin 1% ointment in combination with destructive modalities because it was too recently introduced into the market, compared to topical fluorouracil (5FU) or imiquimod.4

A post-hoc pooled analysis of data from two Phase III, randomized, double-blinded, vehicle-controlled studies of Tirbanibulin 1% ointment was performed to assess its tolerability.5 This analysis included data from adults with AK on the face or scalp who completed the Phase III trials and achieved 100-percent clearance in the treatment area (n=174).

As reported in the study, the mechanisms of tirbanibulin are synthetic inhibitor of tubulin polymerization and Src kinase signaling. Clinically, this translates to promotion of apoptosis as opposed to induction of necrosis, which could potentially result in less clinical incidence of “necrosis” type reactions, such as crusting, swelling, vesiculation/pustulation, and erosion/ulceration.6 The overwhelming majority of the 174 patients in the Phase III studies who achieved complete clearance of the AKs experienced low composite scores of anticipated LSRs, most likely attributed to the proposed mechanisms of action. This post-hoc analysis shows that complete clearance of AK using tirbanibulin 1% ointment was associated with mild-to-moderate LSRs, with 70.2 percent of the patients showing a composite LSR score of 5 or less (Figure 1).5 This suggests that more aggressive reactions were not necessary for induction of clearance. This is supported by the small number of subjects who achieved clearance with higher composite scores.

An important observation from the post-hoc analysis is that none of the subjects withdrew from the studies, with the caveat that after the five-day treatment period, the LSRs were evaluated on Days 8, 15, and 29. In that respect, the LSRs are already in motion by the mechanisms of tirbanibulin and cannot be stopped in the trial, even though in clinical practice they can be mitigated with emollients, topical anesthetics, or other modalities. Moreover, similar to the ingenol mebutate trials of three-day applications, withdrawal from the tirbanibulin trials due to LSRs would not change the outcomes of a patient, compared to other trials with longer treatment times where discontinuation of therapy would eliminate the LSRs.

The results of the post-hoc analysis indicate that clearance does not have to be dependent on aggressive LSRs. This should be used as a discussion point with patients who are both new to topical treatments for AKs as well as those who have experienced negative outcomes. Clearance should also be a function of keeping AKs away, and the durability of response seen in the Phase III trials could improve patient adherence to treatment and encourage repeat courses as necessary. The portion of the study title, “not correlated with the severity of local skin reactions” needs to be understood as not having a grading to match resolution. But the clinician should still be aware of the potential for any patient to develop any grade of LSRs, and this should be part of the discussion with the patient, as well as providing appropriate adjunctive tools to maximize outcomes.

References

- Berman B, Cohen DE, Amini S. What is the role of field-directed therapy in the treatment of actinic keratosis? part 1: overview and investigational topical agents. Cutis. 2012;89(5):241–225.

- Goldenberg G, Berman B, Underhill S. Assessment of local skin reactions with a sequential regimen of cryosurgery followed by ingenol mebutate gel, 0.015%, in patients with actinic keratosis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:1–8

- Yeung H, Baranowski ML, Swerlick RA, et al. Use and cost of actinic keratosis destruction in the Medicare Part B fee-for-service population, 2007 to 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(11):1281–1285.

- Eisen D, Asgari MM, Bennett DB, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:e209–233.

- Berman B, Schlesinger T, Bhatia N, et al. Complete clearance of actinic keratosis with tirbanibulin ointment 1% is not correlated with the severity of local skin reactions. Poster presentation. MauiDerm 2022 for Dermatologists. Maui, Hawaii. 24–28 Jan 2022.

- Chinnasamy S, Zameer F, Muthuchelian K. Molecular and biological mechanisms of apoptosis and its detection techniques. J Oncol Sci. 2020; 6(1):49–64.

Commentary: Emotional and Social/Functioning Impact of Actinic Keratosis on Individuals Living with the Condition: An Exploratory Qualitative Research Initiative in the US

J Clin Aestet Dermatol. 2022;15(10):S15–S16

by Ismail Kasujee, PhD

Dr. Kasujee is Global Head of Real World Evidence (RWE) and Health Economics & Outcomes Research (HEOR) for Almirall SA in Barcelona, Spain.

Funding: Funding for this article was provided by Almirall LLC in Malvern, Pennsylvania, USA.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Kasujee is an employee of Almirall SA in Barcelona, Spain.

The impact of disease burden in patients with actinic keratosis (AK) may not be fully captured by traditional, validated endpoints (e.g., lesion count, Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA], Skindex). As a result, in-depth, qualitative telephone interviews were conducted, with the intent of gaining a better understanding of what really matters to patients in regard to AK treatment.

Patients included in this study were diagnosed with AK and had received recent treatment within the prior 12 months. Telephone interviews were 40 to 60 minutes long and included open-ended questions with concepts related to patient demographics, motivation and specific symptoms prompting patient treatment for AK, and current disease-related skin texture. Patients were questioned about aspects of life (e.g., social, emotional, family life, professional life) most affected by their AK and related treatments. Treatment history and preferences for future treatments were also captured, representing patient preferences and value perceptions and their implications in patient management of AK.

Thirteen eligible patients participated in the research, representing areas across the continental United States (US); 53.8 percent were female; and the average age of all participants was 58.7 years. Additionally, 53.8 percent of the participants were employed, 30.7 percent were retired, and 15.3 percent were unemployed. On average, patients received their initial diagnoses of AK 14.8 years earlier, indicating the chronicity of AK.

Results related to treatment history and patient preferences showed that the majority of subjects (12/13, 92.3%) expressed discomfort due to side-effect/local skin reaction (LSR) severity associated with prior topical treatments, including fluorouracil (FU), and highlighted the impact this had on their social and professional lives. Furthermore, regarding work impact, patients noted “shyness in interacting with others at work” (7/13, 53.8%), as well as some impact of AK and AK treatment-related LSRs on work life (6/13, 46.2%).

“I think it really affects me with friends or strangers if I’m having a sort of episode where I’m having itchiness. I’m just thinking about the keratosis and that sort of puts me in a bad mood…”

In terms of how patients related their treatment history to desired qualities in future treatments, the majority of patients responded to seeking less severe side effects/LSRs (10/13, 76.9%), in addition to shorter treatment length and quicker results (8/13, 61.5%). Some identified the importance of better skin tone and less scarring (5/13,38.5%), and others sought easier application and lower frequency of medication application (3/13, 23.1%, each).

“Hopefully, it would be just as effective and maybe effective in a way that it might not produce scabs and scars… Might not be as aggressive… to hurt the skin…it would be a nice thing to find something that didn’t have to do all that to your skin again…” [Less Severe Side Effects, LSRs]

“If something came along that might be more effective, according to my dermatologist, and at the same time, in less time than that, (and less) stinging…go for it…” [Shorter Treatment Length and Quicker Results]

Motivators identified as key reasons prompting patients to seek AK treatment included skin cancer concerns (92.3%), worsening of AK symptoms (61.5%), concerns about scarring or appearance (46.2%), and influence of family/friends (46.2%).

Aspects of patients’ lives most affected by AK were grouped into three areas—emotional, social/functioning, and impacts on family.

Key attributes within the “emotional impact” domain included worried about developing more serious skin disease (100%), embarrassed/annoyed/frustrated (due to AK) (76.9%), anxious/depressed due to AK (69.2%), feeling isolated (53.8%), and worried about skin appearance (30.8%).

Patients resoundingly expressed concerns related to the progression of AK into a more serious skin disease.

“…a little anxious… there is the possibility that it could turn into actual skin cancer, that’s always in the back of my mind” and also largely voiced that they felt anxious or depressed; “11 out 10 [on a worry-scale], I had some anxiety to begin with and then this [AK diagnosis] just exacerbates that. Also, physicians don’t seem to make as big of a deal about it as I do.”

Key attributes within “social impact/functioning” domain included desire to hide sun damage from others (84.6%), impact on daily activities (30.7%), interactions with others (strangers/friends/family members) (30.7%), giving explanations to anyone about AK/appearance (30.7%), and ability to show affection (30.7%).

Patients predominantly expressed worry about the appearance of their skin.

“I wear long sleeves and am [fully] completely covered up…just being more conscientious about showing skin or, not wanting to because,… can be rough…scaly…discolored …it just doesn’t look pretty…”

Key attributes within “impact on family” domain included family members’ general concern about subject’s AK (76.9%), stress knowing that current AK could turn into something serious (38.4%), and concern associated with presence of family history (of AK) (30.7%).

While viewed from a small patient sample size, the results and qualitative responses provide a striking display of the effects of AK within the emotional and social/functioning aspects of patients living with this chronic and prevalent skin condition. Core themes found here were related to concerns of LSRs, worry, anxiety, and isolation. Beyond the validated endpoints, there may be additional key outcomes related to patient satisfaction and with the aim of gaining clarity into patient preferences, further real-world evidence studies will be needed to help better capture the voice of the patient.

References

- Kasujee I, Narayanan S, Diaz C, et al. Emotional and Social Functioning Impact of Actinic Keratosis on Individuals Living with the Condition: An Exploratory Qualitative Research Initiative in the U.S. Abstract presented at: Maui Derm for Dermatologists Winter Meeting January 24-28, 2022; Maui, HI, USA

- Kasujee I, Narayanan S, Diaz C, et al. Emotional and Social Functioning Impact of Actinic Keratosis on Individuals Living with the Condition: An Exploratory Qualitative Research Initiative in the U.S. Poster presented at: International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Annual Meeting May 10-18, 2022; Washington, DC, USA.